News -

7 ways innovators can protect their IP

A new song; a new character; a new algorithm — in the 21st century, any of these, and many more kinds of new ideas, could make their creator’s name and fortune. That’s the way the creative economy works.

As author John Howkins put it in his 2001 book The Creative Economy: How People Make Money from Ideas, the creative economy refers to the economic potential of activities that centre on creativity, knowledge, and information. That includes design, advertising, research and development, software, and many more professions from the arts, media and technology sectors.

How powerful is this economy? According to the 2018 UNESCO Global Report “Re|shaping Cultural Policies: Advancing creativity for development”, the creative economy generated annual revenues of US$2,250 billion and global exports of over US$250 billion, and provided nearly 30 million jobs worldwide.

Industries that are part of the cultural and creative economy also employ more people aged 15 to 29 than any other sector, and almost half of the people they employ are women. So nurturing this economy unlocks opportunities for gender equity and wealth-building for the younger generation all over the world.

If you are one of the creators driving the creative economy, you already know how important ideas are for propelling your career. You also know that as a creator, you hold the intellectual property rights to your original creations. But chances are, you have encountered hurdles when it comes to protecting these rights. From gaming and graphic design, to music and movies, we sadly find it all too easy to find daily examples of lopsided contracts and industry norms stacking the odds against how much creators can extract value from their own IP.

Information is power. Here’s a breakdown of the tools at your disposal when it comes to safeguarding your ideas.

1. TRADE SECRETS

Any confidential information that gives a business a competitive advantage, that is known to a limited group of people, and that is subject to protections such as confidentiality agreements can be classified as a trade secret. And trade secrets are IP.

A trade secret can be technical (like a manufacturing process), commercial (like a supplier source), or even a combination of publicly available information that when added together and kept confidential, gives a business an edge. Trade secrets are often referred to as proprietary information.

If you are in possession of a trade secret, all you have to do is to keep it a secret. You don’t have to register this information, and there is no time limit for how long you can keep it a secret. However, you also likely will not be able to license it to others for use, which may constrain how much financial value you can derive from this trade secret.

Another disadvantage of trade secrets is that legal protection kicks in only when the secret has been exposed, for example through breach of confidence or espionage. And while these are considered unfair practices, if competitors replicate your trade secret through reverse engineering or independent research and development, there is nothing you can do to stop them from using the information.

2. PATENTS

If you invent a product or process that offers a new way of doing something, or a new technical solution to a problem, then you may consider applying for a patent.

To get a patent, you have to meet several specific conditions, such as the inclusion of a “non-obvious” step. That means proving the invention could not have been obviously deduced by a person who has an ordinary level of skill in the relevant technical field.

Furthermore, you have to disclose the invention’s technical information clearly enough that a person with an ordinary level of skill in the relevant technical field can replicate it. Why? The thinking is that such disclosures are a boon for innovation.

On the plus side, a patent gives the original creator of an invention official recognition, as well as the right to allow another individual or organisation to make, use, and/or sell this invention through licensing agreements. The patent-holder can also sell or transfer the patent to another party, but doing so means losing the rights over the patented invention.

There will be legal protection for the patent-holder if there is any patent infringement, but the onus is on the patent-holder to monitor for infringement and to initiate action when that happens.

Also, a patent doesn’t last forever. Once it expires, the protection for the original inventor ends. A patent is also typically granted only within a country or region, rather than globally.

3. INDUSTRIAL DESIGNS

Defined as the ornamental or aesthetic aspect of an item, industrial designs include the shapes, patterns, lines or colours of objects such as furniture and textiles.

Industrial designs need to meet different criteria and are subject to different legal processes depending on which country you are in. For example, in some jurisdictions, you don’t have to register a design to enjoy some degree of legal protection, while registration is essential in other jurisdictions. The duration of the protection also varies.

Legal protection generally includes the right to prevent others from making, selling or importing items that copy the protected design.

However, as industrial design pertains to useful items (that is, things that have a utilitarian function, such as furniture), their legal status can be ambiguous. Under United States copyright law for instance, useful items are protected by copyright only to the extent that their artistic elements are separable from their utilitarian aspects. If they are deemed purely utilitarian, creators have to seek legal protection through a utility patent, which has stringent requirements, a rigorous application process, and a short duration.

So if you invented the toaster, you can get a utility patent. If you invented a new design for a toaster, you can get protections accorded to industrial design. Although a drawing or a photograph would be eligible for copyright protection as forms of artistic expression, its function, design, or utility would not.

4. TRADEMARKS

Any mark, name, or logo under which trade is conducted for any product or service and by which the manufacturer or the service provider is identified are trademarks and these are also IP. Specific colours and non-visible signs such as sounds or fragrances used in certain particular contexts can also be trademarks.

Another type of trademark is a collective mark, which applies to a group of businesses (usually in the same industry), rather than a single business. Certificate trademarks are another way to communicate credibility, as these indicate that the user has complied with certain criteria, such as standards for sustainable practices.

Trademarks can be registered at the national, regional and international level. A trademark is exclusively used by its owner, and it can be sold to another party or licensed by its owner for another’s use, in return for payment. The term of protection for a trademark varies, but trademark registration can be renewed indefinitely by paying a fee.

5. COPYRIGHT

In most countries, if you have written a book, composed a piece of music, created a painting or made a film, you are automatically granted copyright protection over your creation. There is no need to register your work, although some creators do, and others use the symbol © to clearly show that their work is protected by copyright.

Copyright includes economic rights (the creator can derive financial reward from the use of his work by others), as well as moral rights (which protect non-economic interests, such as the right to oppose changes to a work that could harm the creator's reputation) associated with a work’s expression.

The duration of copyright protection varies, with many countries adopting the standard of 70 years plus the life of the author. Also, copyright protection covers only the expression of an idea, and not the procedures and methods used to express it. A sculptor thus owns the copyright to his sculpture, but not to the techniques he used to make it.

6. GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATION (GI)

This form of protection is for products that have a specific geographical origin, and whose qualities or reputation are explicitly due to that origin. Usually, that means the raw materials for these products are sourced from its place of origin, and they are created and processed in that place as well.

Famous examples of this include champagne, a variety of sparkling wine which can only be labelled as such if it is made in the Champagne region of France. India’s Darjeeling tea is similarly protected by GI.

GI can communicate quality control, as those who use this form of protection typically have stringent benchmarks resulting from a long tradition of making a product. However, producers who are not allowed to use a particular GI are still allowed to use the same benchmarks and techniques as those who are protected under that GI.

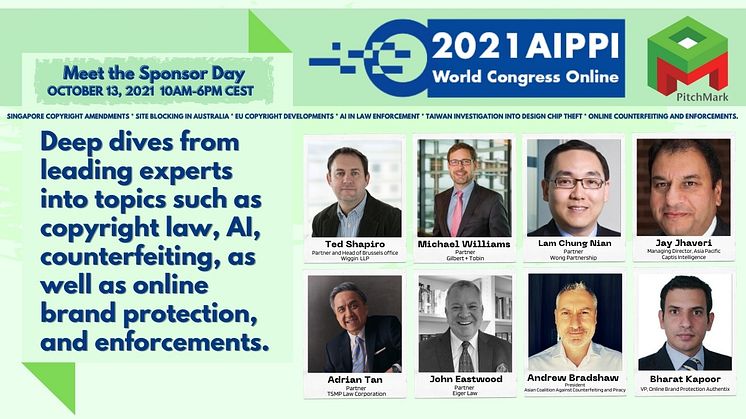

7. PITCHMARK

As you can see, there is a range of IP protections out there, and they are often used in different combinations depending on the circumstances. However, it is also clear that existing protections may not be useful for innovators in today’s creative economy. GIs are relevant to a very specific kind of product, and trade secrets, patents and trademarks also exist in very distinct commercial contexts.

While industrial designs and copyrights are valuable tools for creators, they may not always be applicable for those who generate ideas for pitching. If you are submitting a campaign proposal, a training curriculum, or a concept for a film in the hopes of getting hired for that project by a client, the status of your IP protection can be very ambiguous and very vulnerable. No contracts have been signed, nothing is in production, and the last thing a creator wants to do is to get bogged down in registrations and other bureaucratic red tape at this early stage.

PitchMark aims to plug this gap. For creators who pitch, we can generate a certificate that serves as evidence that you created your pitch materials before the date and time of the certificate. PitchMark can also trace the expression and distribution of original concepts, designs, proposals, business plans and other creative ideas and expressions. Furthermore, the use of the PitchMark logo on your materials also serves as a signal to potential clients that you take your IP protection seriously.

Another valuable benefit of joining the PitchMark community is gaining access to this community. This includes not just fellow creators, but also a community of companies who have signed our pledge to show their commitment to respecting IP rights, as well as a network of legal counsel who can help to protect these rights should the need arise.

The creative economy changes quickly, far more quickly than IP law. As new ideas are born every day for new sectors of this economy, we believe there is a need to build new safeguards for innovators that will ensure they retain their ultimate superpower — the ability to use their creations the way they want them used.

If you are an innovator who pitches, or a client who receives pitches, register with PitchMark here to join our community. If you are a lawyer who wants to help innovators protect their IP, register with PitchMark here.