News -

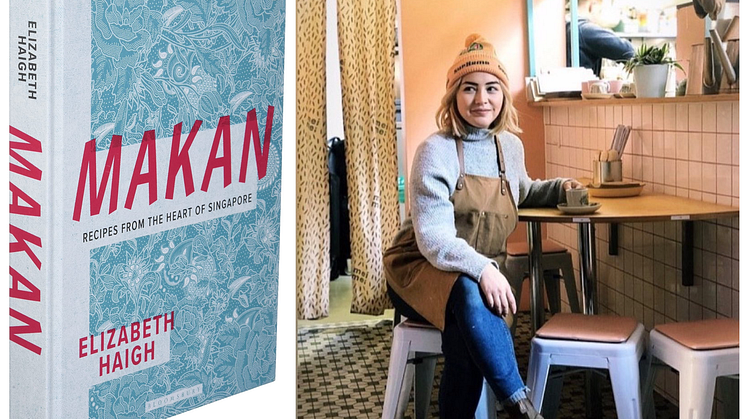

Why this community burned a coat created through IP theft

Today’s fashion plagiarist is spoilt for choice. The Internet is flooded with high-resolution images of the latest designs, and catwalk shows are live-streamed on social media.

Meanwhile, pressure is mounting on brands and retailers to cut costs in an increasingly tough market, and design departments are shrinking. As a result, the perennial problem of copying is becoming even more prolific.

One recent example of this is also believed to be the first time a business has been sued in the United States for copying a traditional indigenous pattern.

In April 2020, Alaska’s Sealaska Heritage Institute, along with family members of the late Tlingit weaver Clarissa Rizal, filed a US federal lawsuit against Neiman Marcus, a Dallas-based retailer, and eleven other retailers for copyright infringement over their marketing of a US$2,555 “Ravenstail Knitted Coat” that appeared to copy a specific robe created by Rizal in 1996.

The Ravenstail term and style has been associated for hundreds of years with Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian tribes.

Clarissa was not only famous for her weaving skills in Alaska but was also named a National Heritage Fellow by the National Endowment for the Arts, the country’s highest honour in traditional arts.

When she died in 2016, her family obtained the rights to the robe. In 2019, they registered the robe with the U.S. copyright office. The copyright was then exclusively licensed to Sealaska Heritage Institute who discovered that Neiman Marcus was selling the coat in 2019.

Protecting a culture

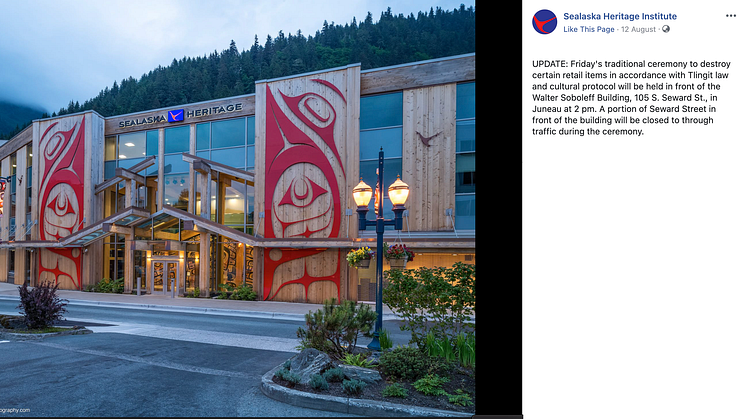

While the lawsuit was settled in March 2021, the community also felt a need for an emotional resolution.

In August 2021, members of the community gathered for an event during which they gave speeches about this case. This was followed by a ceremony, during which Rizal’s family members and community leaders burnt an example of the commercial garment that had copied Rizal’s design.

During the ceremony, Rosita Worl, president of Sealaska Heritage Institute, said: “We resolved it not only in accordance with U.S. law but by Tlingit law and practice. Tlingit law is very clear in protection of our intellectual property.” Another speaker, Ricardo Worl, added: “Taking a name or design violates a sacred law in Tlingit culture.”

In another case involving the appropriation of culturally significant artisanal IP, Indian designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee’s digitally-printed Sanganeri and Kalamkari lookalike collection for fast fashion chain H&M spurred a joint letter by a collective of Indian craft organisations. Their concern: While the collection was marketed as being linked to Indian design and craft, none of it was handmade and none of it was manufactured by any artisan.

Writing about this issue, crafts activist Laila Tyabji asserted: "India is fortunate to have a huge pool of living craft traditions. How we promote it, give craftspeople due respect, make craft a profitable profession, and sensitively preserve cultural identity while bringing it into the 21st century and the contemporary marketplace, is the real challenge. When working with communities that have centuries-old creative traditions and practices, there should be no crude shortcuts, however tempting."