Blog post -

Safeguarding IP of indigenous knowledge may be crucial for the human race

With an estimated 14 to 17 million indigenous peoples, it is not surprising that the Philippines has a legal framework for the protection of indigenous works. For instance, its Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act introduced the concept of community intellectual rights and granted indigenous peoples the right to practice and revitalise their cultural traditions and customs.

However, many of the application processes needed to protect such IP are expensive, complex, and are sometimes not even known to the communities in question. Very often, such regulations also show little understanding of the cultural ethos of the groups that create and sustain indigenous traditions and practices.

Efforts to improve the legal protection of such indigenous knowledge are underway, with one example being the World Intellectual Property Organization’s Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore.

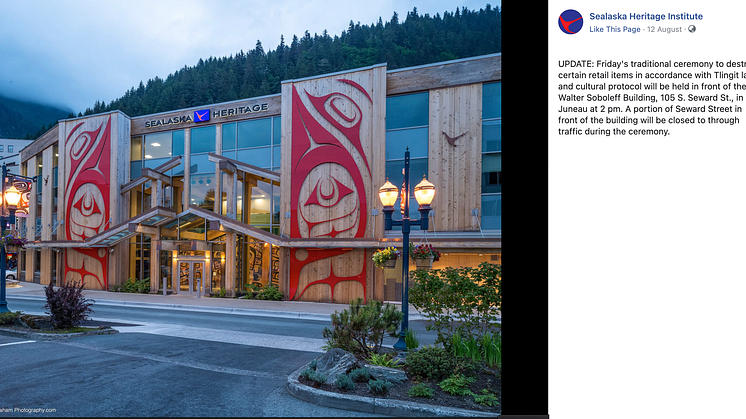

This, and other country-specific legislation, will hopefully help to prevent commercial brands from commodifying indigenous designs of everything from tattoos to textiles, without proper credit and fair recompense.

An existential question

Beyond addressing issues of cultural appropriation, much more is potentially at stake than whether a Gen Z fashionista knows if he is sporting sneakers that reproduce an indigenous design. In an age of climate crisis, indigenous knowledge could be a critical tool for managing extreme weather patterns.

For example, New Zealand’s Māori tribe Ngāti Naho believes that a specific area in the country’s Waikato region is ruled by a water-dwelling creature. When an expressway was being planned for this area decades ago, the authorities rerouted the road in order to respect this belief.

A year later, when the area was hit by a major flood, the expressway was unharmed. In other words, indigenous mythology can be seen as a knowledge system that translates a deep understanding of one’s environment through storytelling.

Increasingly, policy-makers are taking heed of these ancient stories. As the New York Times reports, “Western-trained researchers and governments are increasingly recognising the wealth of knowledge that Indigenous communities have amassed to coexist with and protect their environments over hundreds or even thousands of years.”

Building on this momentum won’t be easy, as the dismissal of indigenous knowledge is deeply entrenched in modern scientific institutions. In Human x Nature, an exhibition about Singapore’s environmental history, the curatorial text notes that from the 17th century onwards, European naturalists, scientists and scholars flocked to the Malay Archipelago to study its flora and fauna.

They “consistently relied on indigenous knowledge and expertise to navigate the region, collect specimens, and identify and name species and their properties and uses. In other words, close collaboration with local communities was crucial to their research and data collection. However, non-European sources were rarely, if ever credited, as they were usually regarded as objects of study, rather than field experts. In addition, European authors wrote with their own biases against indigenous knowledge systems and conventions, often deeming the latter unscientific or superstitious”.

Nevertheless, some of this precious knowledge did survive, and the exhibition itself is testament to how the tide may well be turning. As the world grapples with unseasonable floods and fires of increasing intensity, perhaps the mythical creatures of indigenous lore have many important things to tell us.