News -

Museums are licensing images of ancient relics and other masterpieces. But who really owns this IP?

Celebrating the Lunar New Year in China is an old tradition, but in recent years, it has also become an occasion for using new technology, most notably through the gifting of digital hongbaos (the name for red paper packets containing money) using different e-wallet platforms.

This year, the enterprising fintech innovators of China have come up with yet another new way to mark the festive season. According to the South China Morning Post (SCMP), Alipay has partnered with 24 provincial and municipal museums to offer digital collectibles based on these museums’ artifacts.

These will be yet another instance of tech’s most buzzy trend — non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which are unique cryptographic tokens that deploy blockchain technology. “NFTs are seen as one way of bringing China’s vast quantity of relics into the digital world,” SCMP reports. “According to a recent research report by the Central University of Finance and Economics, 44 per cent of cultural relics in China have been digitalised.”

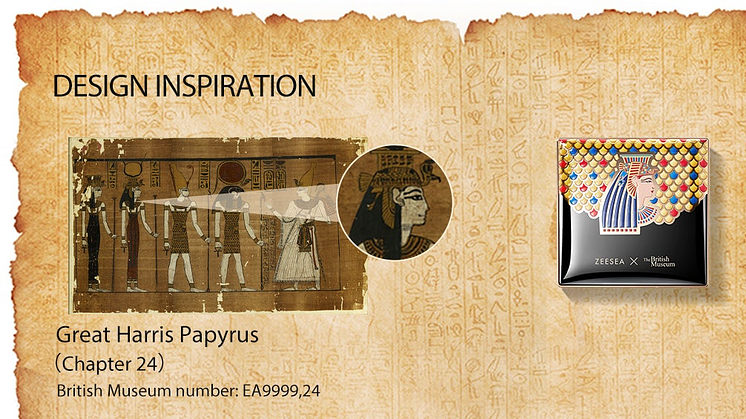

NFTs may be the latest way cultural institutions are trying to monetise their collections, but they are certainly not the first. Those posters and mugs bearing reproductions of famous paintings that you get from museum gift shops all over the world are a common way that such institutions try to generate revenue from this intellectual property.

In fact, The Guardian notes that in 2019, the Uffizi in Italy made about US$1.1 million in revenue from the sale of photos of its collection, while the Louvre in France has teamed up with numerous companies to license images of its collection for different products. In 2020, these partnerships reportedly generated US$5 million for the Louvre. Meanwhile, China’s Palace Museum reportedly took in a whopping US$222 million through similar product sales in 2018.

With visitor numbers falling due to pandemic restrictions, such revenue is a much-needed way for museums to improve their finances. However, some have raised questions about the ways relics and artworks are being commercialised by such institutions.

Dr Grischka Petri, a lawyer and art historian at the University of Glasgow, told The Guardian that “it was problematic that museums were acting as trustees of long-dead artists whose works were no longer in copyright”. In the UK and the European Union, for instance, the copyright for a work of art lasts for 70 years after the creator’s death, after which it typically enters the public domain.

However, in some countries, museums can claim perpetual moral rights of creators’ work. The reasoning for this is that such institutions serve as custodians of a country’s cultural legacy, and such IP ownership gives them more authority when, for instance, they ask companies to remove poor reproductions of an artwork from the market. But licensing images of culturally significant artwork to help cosmetic companies and fast-food chains sell their wares strays quite a bit from this custodial role. So it’s little wonder that not everyone is comfortable with the growing trend of physical and digital products featuring culturally significant IP.

PitchMark helps innovators deter idea theft, so that clients get the idea but don’t take it. Visit PitchMark.net and register for free as a PitchMark member today.