News -

Dua Lipa’s hit song "Levitating" slapped with two copyright cases

British pop star Dua Lipa is facing two copyright infringement cases relating to her smash hit song “Levitating” released during the pandemic. A US-based reggae band has accused her of copying a portion of their song, while two songwriters have accused her of ripping off their decade-old disco songs.

The first claim was made by the US-based Artikal Sound System. It sued Dua Lipa and her label Warner Records alleging that the tune of her song was strikingly similar to their song “Live Your Life,” which was released in 2017 and protected under US copyright law.

The reggae band alleged that Lipa and her team "listened to and copied" their song and later replicated it. They have also demanded monetary damages and a share of profits from the success of her song.

The second lawsuit, filed by songwriters, L. Russell Brown and Sandy Linzer, claimed that Dua Lipa’s song was "substantially similar" to their songs ‘Wiggle and Giggle All Night’ released in 1979, and ‘Don Diablo’ released in the subsequent year. The duo alleged that the pop star used a portion of their song as her signature melody, which went viral on TikTok.

Furthermore, they cited a press interview wherein Dua Lipa acknowledged that she delved into decade-old music to take inspiration for her song. However, it is not known in what way the songwriters want to be compensated for the copyright infringement.

Dua Lipa is yet to comment on these allegations.

These lawsuits are the most recent in a series of legal proceedings involving allegations of song piracy. To gain a better understanding of these lawsuits, we had a brief discussion with Frank Rittman, PitchMark’s Legal Advisor.

What do the plaintiffs need to do to prevail on their claims?

Three things under U.S. law: (1) prove that what was copied was in fact eligible for copyright protection; (2) establish that the defendant had access to the underlying works claimed to have been infringed; and (3) convince the court that the works in question are substantially similar. If any of these three elements fail, the complaint fails. The mere coincidence of separate, independently created works doesn’t establish any basis for infringement.

How can they prove that? What if Dua Lipa never met either of them, or if parts of the songs sound different from one another? What if she can show that she never intended to copy them?

It doesn’t matter if she never met them, it only matters that she had some theoretical means of access to their underlying work. So, if the song was commercially available for purchase on a recording, or available for streaming, or even just played on the radio that’s enough to establish access. In terms of proving similarity, the plaintiffs are subject to both an intrinsic test – meaning would an ordinary person find them to be similar – as well as an extrinsic one. It’s this latter element that requires the plaintiff to demonstrate, often painstakingly, that certain specific elements of the works are the same. It doesn’t have to be the entire song, either, and that relates to the intrinsic test of whether at a gut level ordinary people might think there’s enough similarity in a particular hook or chord sequence for the songs to sound like each other. And finally, there’s no need to prove any intent to copy; courts have determined that plagiarism can in fact be subconscious yet still actionable.

What part of a song isn’t protected by copyright?

It’s the title, for one thing, though that isn’t relevant in either instance here. Beyond that, courts have held that common or trite musical elements also don’t sufficiently merit protection. So, two-note or three-note progressions, in and of themselves, probably aren’t sufficiently original to be eligible for protection and cannot be infringed.

Who makes the final determination? Is it a jury, and if so how and why are they qualified to do that?

Although the Supreme Court has held that civil claims may be tried before a jury under certain circumstances, infringement actions such as this are almost always decided in the United States by a judge, typically through the assistance of trained musicologists brought in by the parties to prove (or defend) their case in terms of similarity. At the end of the day, it’s a factual determination but it needs to be properly supported by a preponderance of the presented evidence.

What’s likely to happen next here?

Well, I can’t say for sure, but the two complaints are quite different in terms of their detail and most litigators have already opined on their practical impact of the pleadings themselves. It doesn’t seem, for example, that Artikal’s complaint addresses any basis of extrinsic similarity. There are no factual claims in their pleadings whatsoever in that regard and when that happens the defendant typically responds by seeking to simply dismiss the complaint altogether without responding to it substantively. But if that were to happen the court would typically allow the plaintiffs a do-over by repleading their case since it would have not been determined on its merits.

Brown and Linzer’s complaint, on the other hand, breaks down the works in question note-by-note for what they characterize as a linear expression of musical tones, so their pleading is at least sufficient on its face to set out the basis of their complaint and the court will be obligated to hear the case should it proceed further.

So far there’s been no response in either case. I imagine part of what’s going on is some full and frank discussion between Dua Lipa, her publisher, and their lawyers about whether to defend against the allegations vigorously or to settle the case(s) for whatever reason and make them go away.

What remedies are available to the plaintiffs if they win their lawsuits? Does it mean they get to own her song if they win?

Remedies for copyright infringement under US law could theoretically include an injunction to prevent further infringement but it's unlikely in this case since the song has been commercially available for more than two years already. A more likely remedy in this instance, given the immense popularity of the work and the millions of dollars in revenues it has generated, would be a monetary award for any past or future earnings. But courts won’t invalidate her copyright.

What happens if she wins instead?

Again, it's difficult to say at this point but a typical remedy for her might be the recovery of any legal fees she had to pay to defend herself against what could ultimately be considered a frivolous claim. And once litigation starts people have to be careful about what they say publicly to ensure consistency with their sworn testimony so that they’re not later accused of perjury or defamation.

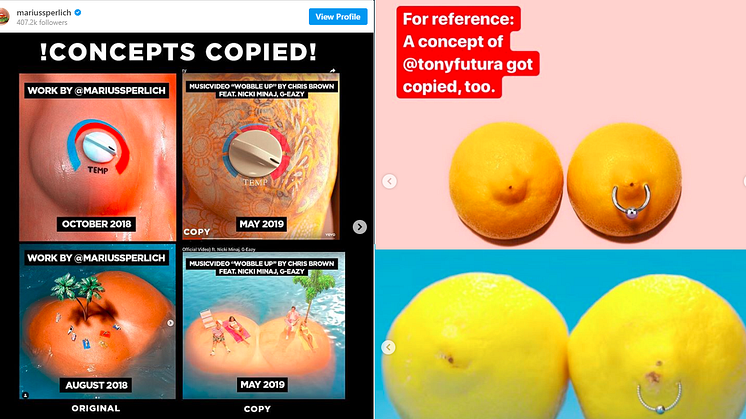

Are these sorts of lawsuits common?

She’s certainly in good company! Recent and famous cases alleging similar claims have involved Ed Sheeran, Katy Perry, Led Zeppelin, Radiohead, and George Harrison among others. Nor is copyright infringement limited to musical compositions…books, movies, photographs, designs…if it can be expressed, it can be infringed.

What should songwriters do to prevent other people from suing them?

Great question! If there’s an answer to that please let me know!! Ed Sheeran said he’d start filming his songwriting sessions as a form of pre-emptive defense against future infringement claims but frankly, I’m not sure how that would help him given what we’ve just discussed.

But a basic first step for fledgling songwriters would certainly be to understand that just because you hear something doesn’t mean you’re free to copy it.

PitchMark helps innovators deter idea theft, so that third parties that they share their idea with get the idea but don’t take it. Visit PitchMark.net and register for free as a PitchMark member today.