News -

Can UNFPA’s “bodyright” initiative stop women from getting abused in the virtual world?

UNFPA, a United Nations sexual and reproductive health agency, wants to change the way women are treated in the virtual world and is urging them to join their global movement.

The internet provides an important space for women who want to express themselves and garner professional opportunities. However, this access acts as a double-edged sword because they disproportionately face all forms of online violence from harassment, doxing, and toxicity to bullying, misinformation, and defamation, all of which can have a detrimental effect on their mental health.

To put things into perspective, a study by the Economist Intelligence Unit in March last year regarding online violence against women, that covered 51 countries and 4,561 women in the survey, highlighted that about 85% of women with access to the internet witnessed online violence against other women, and 38% have actually experienced it personally.

Moreover, about 65% of women surveyed have experienced cyber-harassment, hate speech and defamation, while 57% have experienced video and image-based abuse, where damaging content is shared concurrently across platforms.

The world has figured out how to protect intellectual property. Companies and platforms have developed methods to identify infringements.

When someone infringes on music or film copyright, digital platforms remove the content immediately.

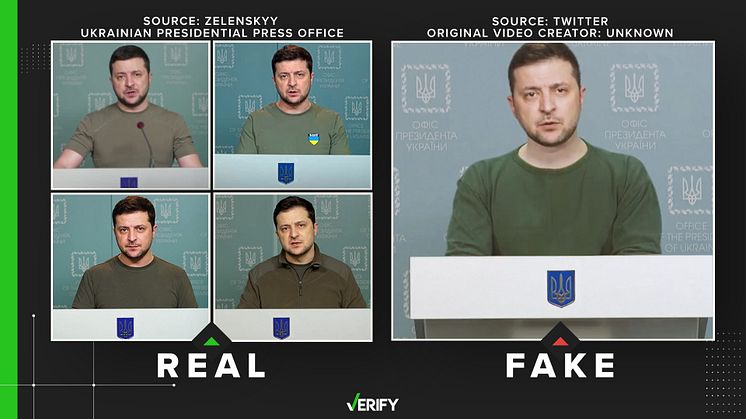

But there are no laws to tackle when an image of a person is misused. Even though tech platforms are committed to improving their systems to tackle online abuse, and they do have an option for reporting, it is inconsistent and very slow, which can do a lot of damage to their mental health before any action is taken by the platform.

They may take an adverse step or, at the least, consider withdrawing from these platforms that have the ability to connect with the world, and can even affect their ability to earn money where their income is dependent on reaching online audiences.

So, if the intellectual property can be protected by copyright, patents and trademarks, it is also possible to protect body images of people, argues UNFPA.

The agency is urging policymakers and technology companies to take digital violence seriously and come up with a legislation and solution using their experience and skills.

To begin the movement in that direction, UNFPA launched a global initiative in December last year to emphasize the importance of bodily autonomy in the virtual world.

It is exploring the possibility of using a “bodyright” mark with a symbol ⓑ that is applicable to photos of bodies online, which is a kind of copyright with symbol ©.

The intention of using the “bodyright” mark on bodies online is to help address issues around the use of images without permission.

It insists that images of bodies should be given the same respect and protection online as copyright gives to music, film and even corporate logos.

To understand whether a bodyright law can be implemented or can it even have a legal standing, PitchMark legal advisor Frank Rittman has shared his views below.

FR: As I understand it, the UNFPA defines “digital violence” rather broadly, covering a wide swath of behaviour that doesn’t necessarily involve photographs of bodily images. That said, sexualized abuse in the form of non-consensual sharing of intimate images, or so-called revenge porn used in cyberbullying, cyber-flashing and the like is certainly a relevant concern and this initiative seeks to build awareness about what they call bodily autonomy, or the right of every individual to choose what they do with their bodies and to live free of fear and violence. Who can argue with that?

Of course, photographs are intellectual property, so the copyright owner of any indiscreet images already has a means under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) to ensure their effective removal from online sites. So if for any reason the pictures in question are “selfies” that have somehow gone astray there’s already an existing remedy for the copyright owner. The problem is that the aggrieved victim in these cases isn’t usually the party taking the photographs, and therefore doesn’t own the copyright(s) in them. And I think that’s exactly the point they’re trying to raise with this initiative.

By now there are standard takedown procedures beyond the DMCA that virtually every social media site has already enacted to address situations like this. Of course, things could always work better, and the problem is further compounded by the Communications Decency Act, which states that web platforms operating in the United States are not legally responsible for user-generated content.

I suppose the idea is for the ⓑ symbol to represent an attestation of authorization that the photo appears with the consent and approval of the photographed subject. That’s easy enough to do if you’re posting photographs of yourself, however revealing. And I suppose that helps distinguish approved images from non-approved images posted by others. But I’m not sure what it does to prevent someone bent on engaging in revenge porn from simply affixing the symbol onto whatever it is that they’ve posted.

As a voluntary initiative intended to raise awareness for personal freedoms and privacies, I have no quarrel with it and wish them the best of luck with this important issue. But presently there’s no legal significance to the ⓑ symbol so I guess I wish them luck with that too.

PitchMark helps innovators deter idea theft, so that third-parties that they share their idea with get the idea but don’t take it. Visit PitchMark.net and register for free as a PitchMark member today.